Featured Image: Breakfast on the Fourth, Lewis & Clark Campground.

Road Trip for Cassandra

Thursday, the First:

Snohomish to Hood River Campground, Washington

C

assandra Tate (1945-2021) and I met at a HistoryLink writers’ meeting held at Seattle’s Virginia Inn several years ago. The way strangers are introduced at a meeting where there is no opportunity for follow-up.

This year, a one-sided opportunity came when I read her obituary published by Harvard College, of a 1977 Nieman Fellow.

“She wrote more than 200 essays for HistoryLink before turning her interest in missionaries Marcus and Narcissa Whitman into the book “Unsettled Ground: The Whitman Massacre and its Shifting Legacy in the American West,” which was published by Sasquatch Books in November 2020.”

The Whitmans’ story has been of interest to me since visiting the Whitman Mission National Park on my move to Seattle from Boston, around the time Cassandra was in attendance at Harvard.

On page 20 of her book, I learned about the Tamastslikt Cultural Institute and made plans to visit. Family logistics opened the Fourth of July weekend for my road trip. The solo trip was a definition of serendipitous.

Found a nice spot at the Hood Park Campground, a US Army Corps of Engineers’ green grass oasis alongside the Snake River and practically under Interstate 12.

Driving downhill 300 feet to the beach with a full load of beach toys.

Friday, the Second:

To Tamastslikt Cultural Institute,

then to Emigrant Springs Campground

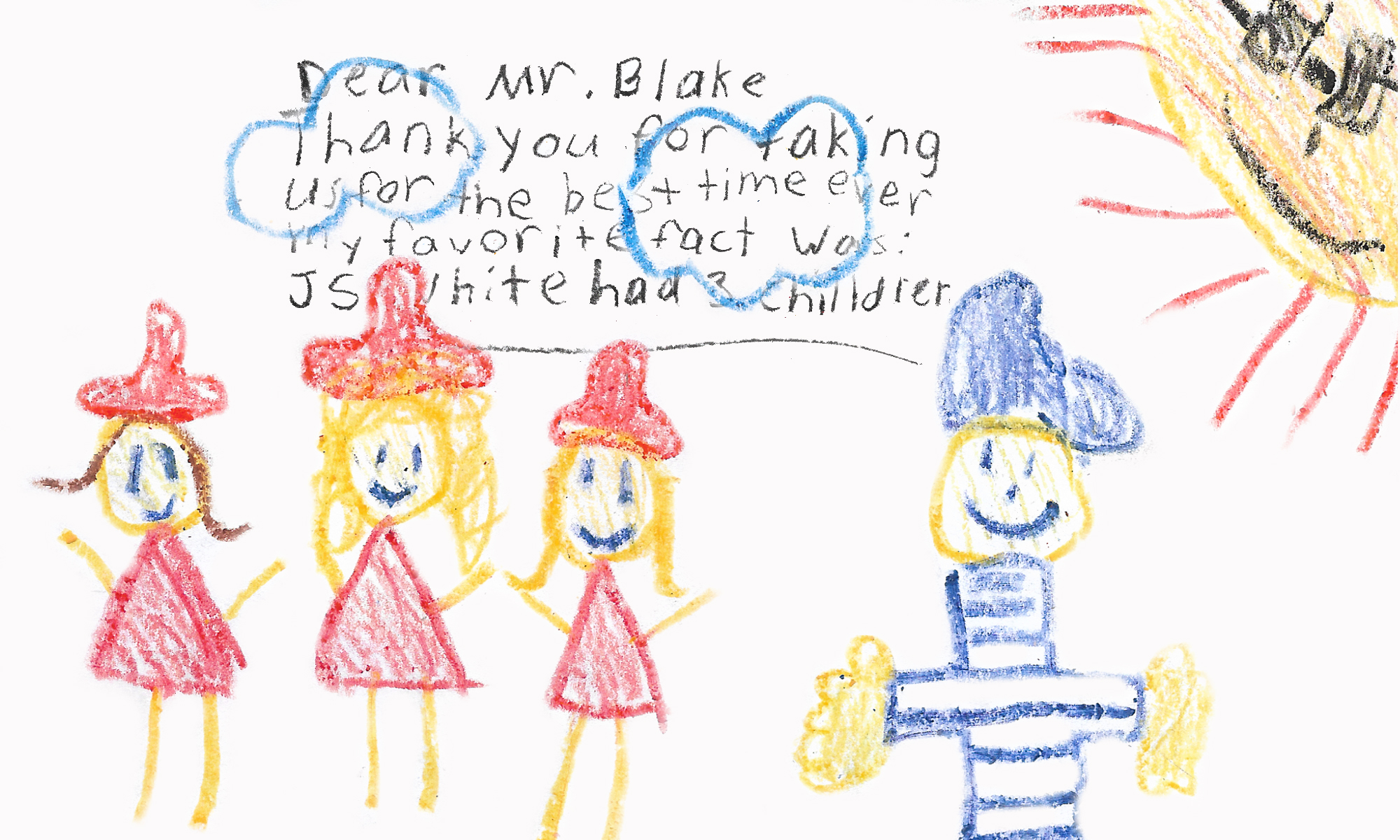

In Chapter Two, “The Imperial Tribe,” Tate introduces us to Roberta Conner, who, as a seventh-grader living in the small town of Coulee Dam, heard about the “Whitman’s Massacre” for the first time — in 1968!

“The story was a standard unit in the Washington State history curriculum for public school students.” (p.19)

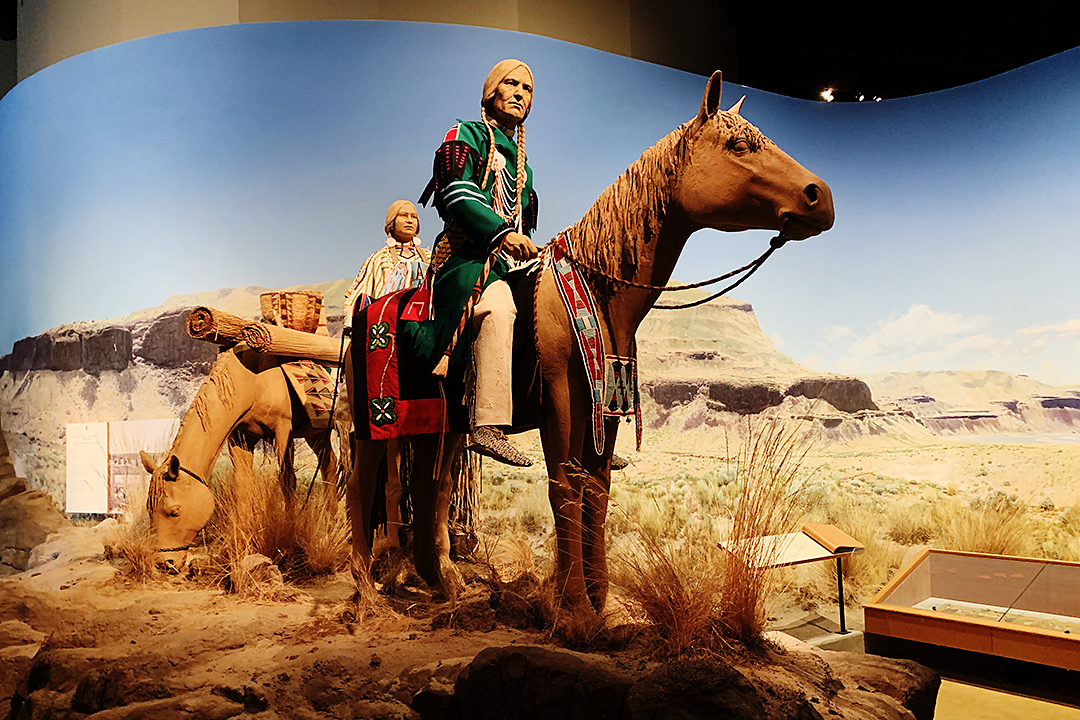

Conner went on to become the founding director of the Tamastslikt (pronounced Tah-MUST-licked) Cultural Institute 30 years later. Located on the Confederated Tribes’ reservation near Pendleton, the institute is the only tribally owned museum and interpretive center on the Oregon Trail.

Tamastlikt takes its name from a Sahaptin word meaning to turn over or interpret. “The main exhibit space is divided into three sections: ‘We Were,’ ‘We Are,’ and ‘We Will Be.'” A recurring theme is the tribes’ relationship to horses,” Tate writes on page 229.

Institute or Museum? It holds a gorgeous exhibition.

Arrived early enough at the Emigrant Springs State Heritage Campground to have a decent selection of available sites. By nightfall, all spaces were taken yet recreational units under-tow continued circling the large campground.

Located off non-stop Interstate 84, on the site of the Oregon Trail, I am trying to fall asleep to the white noise of Divine Retribution.

Saturday, the Third:

To Whitman Mission National Park,

then to Lewis and Clark State Park Campground

Broke camp with the morning light just finding its way through the woods and reached the national park sleep-deprived. I bedded down under the shade of a small tree, in the thick green grass of the park’s grounds and fell into a deep sleep to a chorus of birdsong.

The modest exhibition in the Visitor Center suffers by comparison with Tamastikt. And a short movie with actors playing the roles of Narcissa and Marcus suffers in comparison with Tate’s flesh and blood account of the couple on the pages of her book.

The takeaway from my first visit to the park over 40 years ago: the Whitmans’ mission changed from converting the Indians to helping the settlers moving west.

In Chapter Six: “Mutual Disillusionment,” I learned that Whitman returned to Boston in 1843, to save the existence of the mission which was $80,000 in debt. He pitched to the leadership of his church – “that Waiilatpu (the location of the mission) was a strategic rest stop and resupply station for travelers to Oregon and that the Papists (Catholics) would take it over if the Prosentants abandoned it.” (p.148)

With funding secured, Whitman met with Horace Greeley, the influential editor of the New York Tribune, who called him “the roughest man we have seen this many day” but also “a man fitted to be a chief in rearing a moral empire among the wild men of the wilderness.”

Whitman joined a wagon train in Saint Louis numbering 120 wagons and up to 1000 emigrants … and the first of the wagons rolled into the mission in late September 1843. “The watching Cayuse must have been stunned,“ Tate writes and ends the chapter with the confirmation that while Whitman was discouraged by his lack of converting Indians, he had found a new mission.

“The Indians have in no case obeyed the command to multiply and replenish the earth, and they cannot stand in the way of others doing so,” Marcus wrote to Narcissa’s parents.

And I secured the last available site in the campground at the Lewis & Clark Trail State Park, less than an hour distant from the Whitman Mission. This dense, green campground commemorates Lewis & Clark’s campsite alongside the Touchet River on May 1, 1806.

Sunday, the Fourth:

To Weinhard Hotel, Dayton, Washington

Woke to another beautiful morning under the “heat dome.” By ten o’clock I was ready for a dip in the Touchet River — a baptism of the Lewis & Clark faith in History. And a blessing to the serendipity of camping within the echo of their footfalls on Fourth!

Artwork of the Patit Creek Encampment outside Dayton, WA.

Tate followed the Lewis & Clark Expedition through Washington State on HistoryLink.org. This is an excerpt from her final Timeline Essay, “Homeward Bound ….”

“The shortcut took them through the present-day towns of Prescott, Waitsburg, and Dayton. There were enough small streams to provide them with water, but by the time they reached Dayton, on May 2, 1806, they were short of food. The hunters brought in only one deer that day — limited fodder when divided among the entire party.”

. . .

And I am homeward bound, inspired, Monday morning: the Fifth of July.